Skies Recovered During the Post-Conflict

In order to discover Colombia’s rich bird wildlife, you don’t have to leave the city. One November morning, in the heart of Bogota, an experienced reporter and a talented illustrator went out together to see the endemic birds of the capital and discovered unexpected stories from around the country.

They are shaped like a boomerang. They pass by quickly. They make elliptical movements in the sky. They chase each other and their fast silhouettes, with their wings held back, resembling two MiG-15 planes in combat. “They’re called swifts”, explains Alejandro Pinto, a 32-year-old biologist from the National University and the guide of this expedition who has been a “birder” for a decade.

It’s 5:50 in the morning, so the night has already gone, but you can’t say it’s daytime. A weak blue light creeps across the sky, barely enough to distinguish the shapes of the birds, the mountains or the glen. Just a few minutes ago we were traveling along a winding dirt route, where the mist offered a milky panorama and the lights of the truck barely allowed us to see a couple of meters ahead. It was the last stretch to the buffer zone of Chingaza Park, the area adjacent to the natural reserve. It was the final destination of a tour that started an hour and forty minutes earlier, in the city of Bogota.

Alejandro takes his equipment out of the truck: a telescope, binoculars, a laser pointer and a huge ornithology book. The water coming down the gorge sounds like loud static, while above, the swifts whistle intermittently and sharply. Alejandro watches them. The flight between of the two birds is agile; they make tight turns, get lost in the vegetation and come out again. The biologist says their name in Latin: Streptoprocne rutila. He also says that it is a very common bird, so although it is beautiful and its flight is a show in itself, it is not the main attraction of this visit, in which he - and therefore us - would like to see a yellow-eared parakeet or, in scientific terms, a Pyrrhura calliptera, which is an endemic species, i.e., it only inhabits the eastern mountain range of Colombia.

We take a few steps forward and Alejandro points the laser towards some bushes. He sets up his tripod and focuses the telescope. Then he whistles and they respond from the bushes. There are two Myioborus ornatus, small birds with black and yellow plumage on their body and a white patch on their face, which are known as candelitas copetiamarillas. Then, we see a cucarachero pechigris (grey-breasted wood wren) and immediately after, we see a Slaty-backed Chat-Tyrant with red plumage on its belly.

In just in a few meters we have observed four different species and that’s not only because of Alejandro’s sharp eyes and ears, but also because Colombia is home to almost 20 percent of the bird biodiversity on the planet. Out of the nine thousand species in the world, a little more than 1,900 are found in Colombia.

You may also like: Five unbeatable reasons to go birdwatching in Colombia

That’s why it is not surprising that this year, in May, the country was the winner—for the third consecutive time—of the Global Big Day, a world event in which observers, experts and amateurs alike, go out to watch birds and register their findings during one day. On this occasion, 1,574 species were sighted, while Peru and Ecuador ranked second and third, with figures that reached 1,486 and 1,142 respectively.

It is precisely because of this enormous variety that the country has great potential as a as a birdwatching destination, to the point, that according to the Conservative Strategy Fund, this activity could attract 278,850 observers each year. However, Alejandro says that, although he continuously provides his guide services for small groups of travelers, this industry is still incipient if compared to that of other countries such as Ecuador, Peru or Brazil. Luis Ureña, owner of Manakin Nature Tours, agrees with that. He gives an example to to help us understand the path covered and the potential to be developed: “For example, Costa Rica has been living off birdwatching for about 35 years and this country is about 15 times smaller than Colombia, and with half the biodiversity we have, but there can be two thousand people watching birds every day, while we, which are one of the largest companies in the country, can receive a maximum of 64 people during birdwatching season”.

Now, the cold Andean forest reveals itself with the clarity of the day and is filled with a multitude of songs. It’s 6:30 in the morning and we climb up the trail until Alejandro stops. A little higher the whistle can be heard. It is a sequence of short sounds as if someone repeatedly pronounced the letter S or, better, like the noise made by a loose metal ring around a screw.

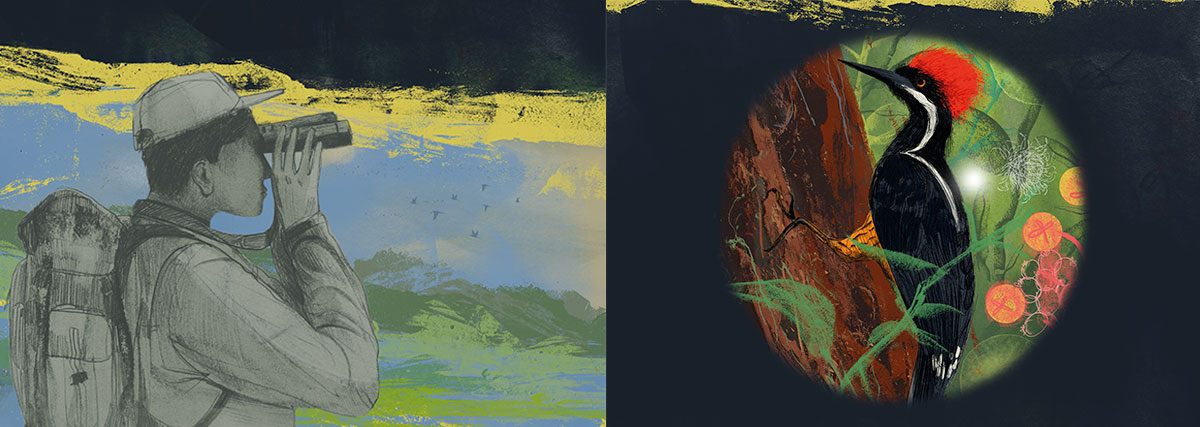

“It is a Hemispingus superciliaris or Hemispingo Cejudo,” he says, and then offers us the telescope focused at eight times magnification. Through the eyepiece we can see the bird and also the reason behind its name: it has a fringe over the eye, like some kind of thick white eyebrow. The guide smiles. Watching birds, recognizing them, collecting them in memory, is the very essence of the birdwatcher, who travels long distances to have fleeting encounters, to appreciate for an instant those elusive animals and complete lists of exotic species that allow him to witness the colors and shapes that evolution and genetics have molded. Luis Ureña sums it up like this: “It’s like completing a sticker album. For example, I still haven’t seen the Black-necked Red Cotinga and that bird becomes my goal. That’s why people who come to see birds arrive with lists of 200 or 250 species and they get very excited every time they find a new one”.

You may also like: Chiribiquete, Colombian Amazon Treasure

Each place has its own ‘stickers’ to complete that album, and the rarest ones are of course the most coveted. Alejandro insists that here, the main prize would be the brown-breasted parakeet, which we can hear now with its distant gurgling. The guide listens attentively and turns, then points to a small valley that opens out between the hills. We can see a small group of these animals, which are just points in the distance. Alejandro takes his cell phone out of his pocket, opens a sound file with bird songs and looks for the call of the parakeet. He plays it, but there is no answer. However, he knows that we are close.

What we are doing today, just less than a couple of hours from Bogota, started to be done in several areas of the country some time ago, and there are already several birdwatching routes that cover regions such as the Andean, Pacific, Atlantic, Magdalena and part of the Amazon regions.

Although there are several challenges in order to develop birdwatching, this industry not only promises to be profitable in economic terms, but also in social and environmental terms. And that’s because many of the places that offer the greatest biodiversity are located in territories that were affected by violence and depended, to some extent, on illegal economies.

That is why foundations, investors and the State itself, are betting on developing projects with communities in remote areas, as they are doing, for example, in Playa Rica, in the department of Putumayo. A training process began there with the inhabitants and it will continue during 2020; investments in infrastructure are also being made to support a community that decided to take care of their natural resources and live from them. “There are 22 families that live in a territory of 488 hectares and most of them used to grow coca. Now they don’t hunt or have coca or cut down the forests for livestock farming. They are now taking care of the ecosystem”, says Michael Quiñones, of the Quinti association, one of the entities that accompanies this process.

Did you know that an endemic species is one that cannot be found naturally in any area other than where it has been recorded?

The same could be said of communities in La Macarena, Meta, or Manaure, in Cesar, where 20 former FARC guerilla fighters decided to set up Tierra Grata Ecotours, a travel agency that offers this type of tour packages.

It is precisely with these projects that many ex-guerilla fighters have found an alternative to put into practice the knowledge they acquired during the time they traveled through in the Colombian jungles, because, as Luis Ureña explains, “since many of these people spent so much time in the mountains, they learned from nature in an empiric way. Therefore, they became very good bird trackers, watchers or listeners. They have a talent they didn’t know they had. There are many of them in the Amazon or Caqueta and we work with some of them”.

But birdwatching tourism in Colombia not only offers them opportunities to work as guides, but allows them to play other roles in the same industry. They can also play other roles. Such is the case of Henry, who was in charge of the FARC telecommunications in the south of Meta and today is in charge of transporting tourists in his truck. “It is an excellent source of income; you can have a good quality of life if you work seriously during the tourist seasons. That’s how I can pay for my son’s university”, he says and then adds: “It is a good way to move forward in the post-conflict: having people working in those areas, because they know them very well”.

We see a roadside hawk, then an Andean Guan and a Quetzal. A Quetzal is an extraordinary creature: its plumage is green on its neck and head, red on its torso, white on its tail. It seems to be covered by a shiny metal color. It is not endemic, but what does it matter, its beauty is unbelievable.

Then we see a beautiful woodpecker drilling into a tree trunk with its beak. Alejandro smiles again. We smile too.

We go on. The guide doesn’t want to give up.. We climb up the trail and stop under a bunch of trees that shade the path. The determination of the guide has its reward: he has just heard, again, the song of his parakeets. Alejandro puts his tripod on the ground. He focuses. One, two, three parakeets get out of the hollow of a very high tree trunk. They are green with a yellow line on the edge of each wing. They stay perched on the branch. Then they take flight and disappear. The encounter is fleeting in time, but everlasting in our memory.

Text by Julián Isaza